California Partners in Flight Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Bird Conservation Plan

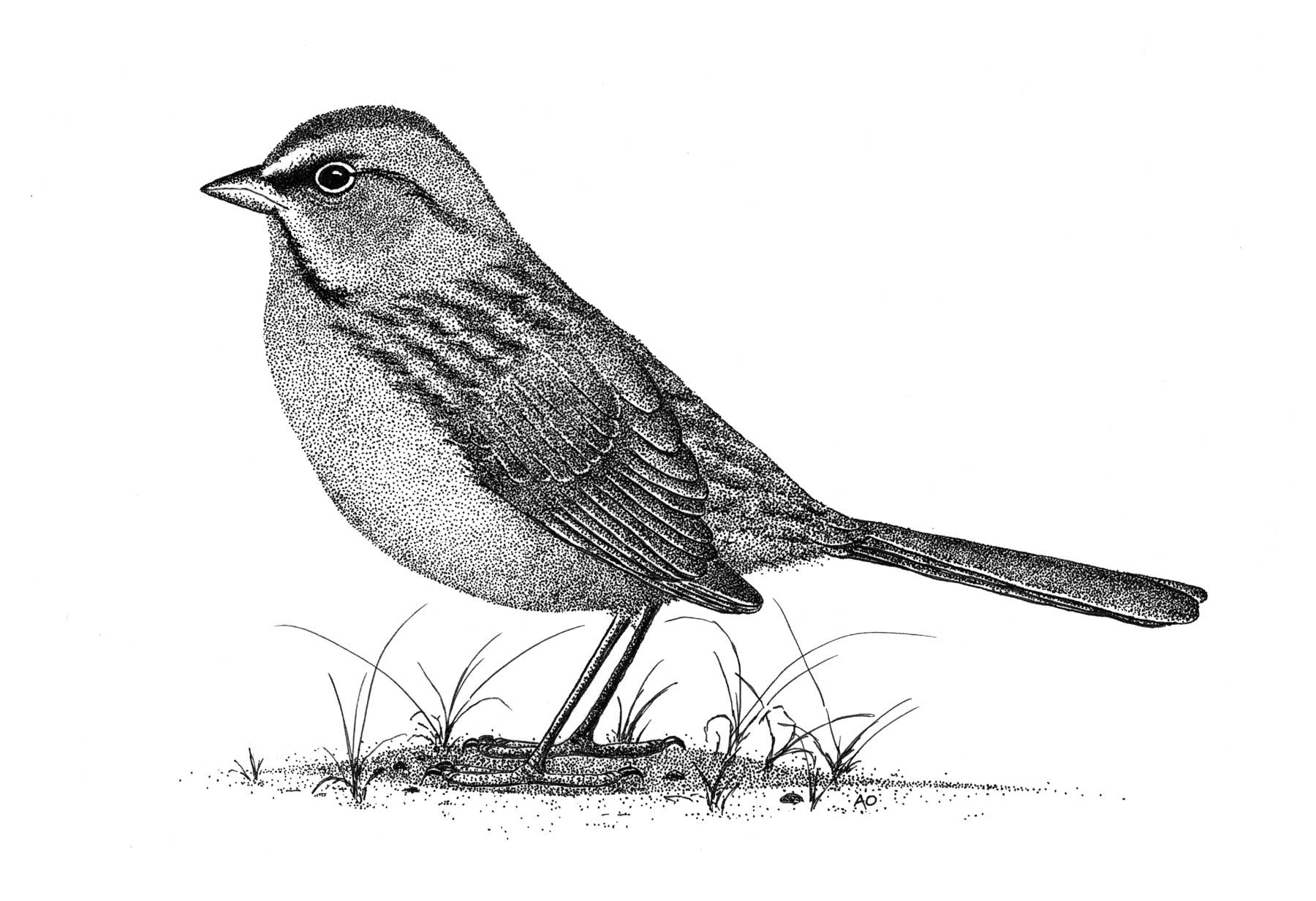

Rufous-crowned Sparrow (Aimophila ruficeps)

Illlustration by Adrienne Olmstead

California Partners in Flight Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Bird Conservation Plan

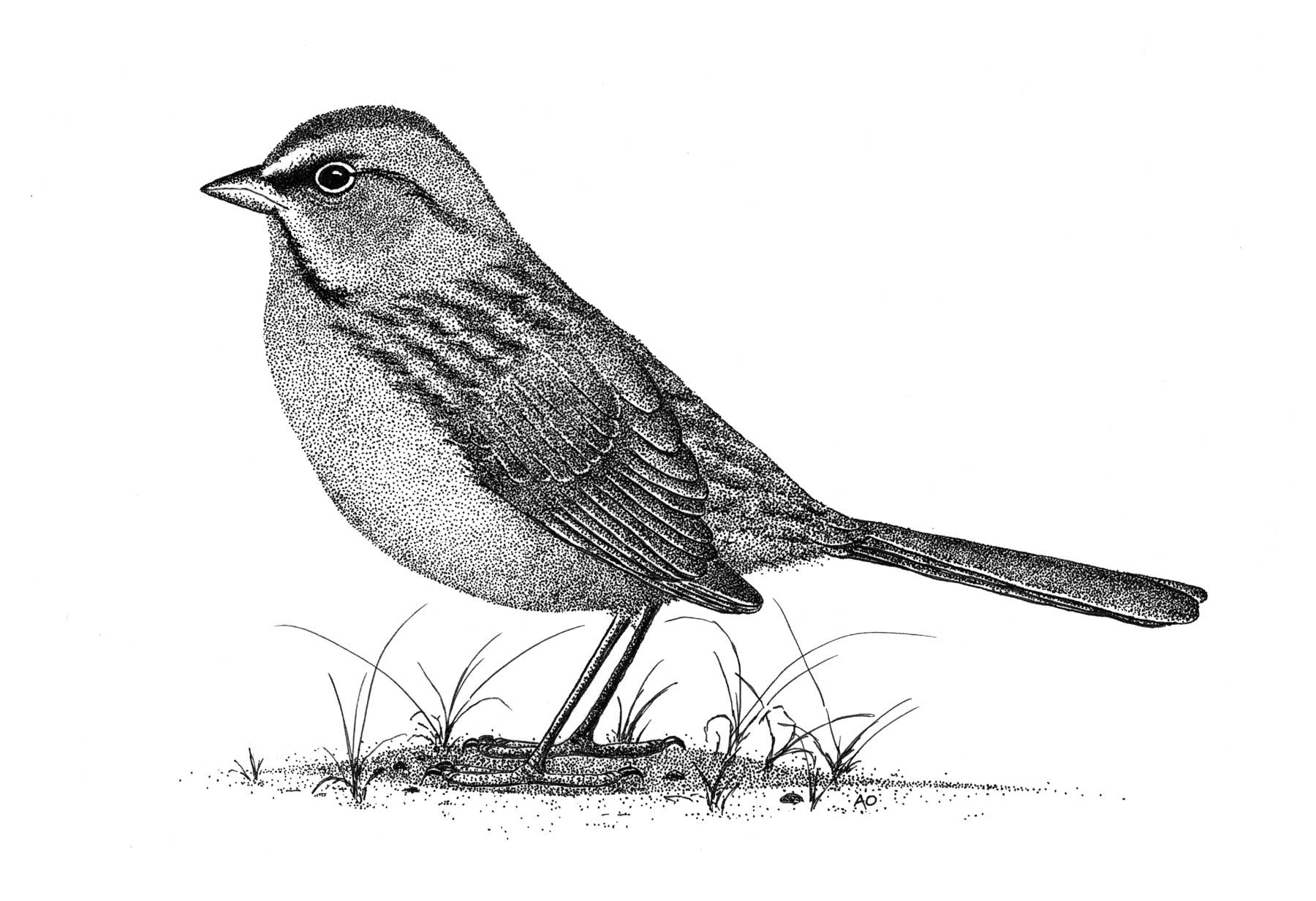

Rufous-crowned Sparrow (Aimophila ruficeps)

Illlustration by Adrienne Olmstead

Prepared by: Nellie Thorngate (nellithorngate@ventanaws.org) and Monika Parsons

Ventana Wilderness Society's Big Sur Ornithology Lab

HC 67 Box 99

Monterey, CA 93924

RECOMMENDED CITATION:

Thorngate, N.and M. Parsons. 2005. Rufous-crowned Sparrow (Aimophila ruficeps). In The Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Bird Conservation Plan: a strategy for protecting and managing coastal scrub and chaparral habitats and associated birds in California. California Partners in Flight. http://www.prbo.org/calpif/htmldocs/scrub.html

SHORTCUTS:

SUBSPECIES STATUS:

There are currently 17 recognized subspecies of the Rufous-crowned Sparrow, five that occur in the United States and 12 that occur in Mexico (Collins 1999). Of the five subspecies that occur in the U.S., two inhabit the desert southwest (A. r. scottii and A. r. eremoeca) and four are found in California (A. r. canescens, A. r. obscura, A. r. ruficeps and A. r. scottii). A. r. ruficeps is a year-round resident of central California from the coast to the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada. A. r. obscura inhabits Santa Cruz Island, Anacapa Island and formerly Santa Catalina Island. A. r. canescens is a resident of southwest California on the slopes of the Transverse and Coastal ranges from Los Angeles County south to Baja California Norte. A. r. canescens can also be found on San Martin Island. California populations of A. r. scottii are found only in isolated portions of the desert mountain ranges of southeastern California (Grinnell and Miller 1944, Collins 1999).

MANAGEMENT STATUS:

A. r. canescens is listed as a California Department of Fish and Game species of special concern (CDFG 2004).

DISTRIBUTION:

Rufous-crowned Sparrows are year-round residents throughout their range, although they descend to lower elevations outside their normal range during severe winters. The species range is discontinuous, including many small and isolated populations throughout the western United States and Mexico (Collins 1999).

HISTORICAL DISTRIBUTION:

California: Four subspecies of Rufous-crowned Sparrow bred historically in coastal California from Mendocino County south through northwestern Baja California Norte, in the coastal slopes, foothills and interior valleys of the Coast, Transverse, and Peninsular ranges. Inland, Rufous-crowned Sparrows could be found breeding from Shasta County south through the western Cascade and Sierra Nevada foothills, southwestern Kern County, and in Joshua Tree National Monument's Coxcomb Mountains. In southeastern California, populations were documented in the Granite, Providence, and New York Mountains of eastern San Bernardino County. Additionally, the subspecies A. r. obscura bred on Santa Cruz, Anacapa and Santa Catalina Islands off the coast of southern California (Grinnell and Miller 1944, Collins 1999).

Outside of CA: Throughout the United States, the Rufous-crowned Sparrow was resident in Washington County in southwestern Utah; throughout Arizona; southern through northeastern New Mexico; in Otero, Bent, Las Animas, and Baca Counties of southeastern Colorado; in Cimarron County and throughout central Oklahoma; throughout much of northwestern Texas; and at Lehman Caves in Great Basin National Park, in White Pine County, and in the Spring Mountains west of Las Vegas in Clark County, Nevada (Miller 1941, Collins 1999).

In Baja California and Mexico, Rufous-crowned Sparrows were resident in the

northwest portion of Baja California Norte (north of 30 N latitude) and in the

Sierra de la Laguna Mountains of Baja California Sur, as well as on Isla de

Todos Santos and Isla de San Martin and from eastern Sonora, western Chihuahua,

and north-central Coahuila, south through much of Mexico to central Oaxaca,

with an isolated population in southern Tamaulipas (Collins 1999).

CURRENT BREEDING DISTRIBUTION:

The current breeding distribution largely matches the historical breeding distribution, with the following exceptions:

Southern California populations of Rufous-crowned Sparrow are increasingly

restricted due to urbanization and agricultural development in Los Angeles,

Orange, Riverside, San Diego, and San Bernardino counties (Collins 1999). Island

populations have suffered significant declines although it appears that members

of the species have colonized Anacapa Island in the Channel Islands in recent

years (Power 1994). Rufous-crowned Sparrows (A. r. obscura) have not

been observed on Santa Catalina Island since 1863 (Grinnell and Miller 1944),

and populations on Todos Santos Island in Baja California have not been observed

since the 1970's (Collins 1999). Rufous-crowned Sparrows have not been observed

on Baja California's Islas de San Martin since they were first detected there

in the early 1900's (Collins 1999).

ECOLOGY:

AVERAGE TERRITORY SIZE:

Average territory size in California chaparral ranges from 0.89 ha to 1.5 ha (NatureServe 2005, Collins 1999). Seven years after a fire in southern California chaparral there were 12 territories per 40 ha (Collins 1999). Plots of burned chaparral three to five years after a fire in southern California supported 2.5-5.8 territories per 40 ha, while coastal scrub plots of similar size supported 3.9 to 6.9 full season territories per 40 ha (Collins 1999).

TIME OF OCCURRENCE AND SEASONAL MOVEMENTS:

Rufous-crowned Sparrows are generally year round residents that do not exhibit true migratory behavior (Collins 1999, DeSante and Geupel 1987). Few data exist on the timing of the onset of breeding; the earliest report of birds carrying nesting material was March 2 in southern California (Collins 1999). Little information exists on juvenal dispersal; young have been observed dispersing into adjacent marginal habitat during fall to early winter (Collins 1999).

FOOD HABITS:

FORAGING STRATEGY:

Rufous-crowned Sparrows forage on or very near the ground while walking or hopping under shrubs or within dense grass or herbaceous cover (DeSante and Geupel 1987). They occasionally forage in weeds and low bushes, but rarely in open areas. Occasionally, Rufous-crowned Sparrows have been observed foraging in the foliage and on the branches of taller woody vegetation such as shrubs and short oaks. During the breeding season, they glean insects from low shrubs, grasses and herbaceous vegetation. Rufous-crowned Sparrows actively forage throughout the day, typically obtaining most of their food by pecking or rarely by scratching through leaf litter (Collins 1999). Occasionally, Rufous-crowned Sparrows obtain food from grasses and the low branches of shrubs by hopping. They will sometimes forage in pairs during the breeding season and in family-sized flocks in late summer and early fall. In winter they can occasionally be found foraging in loose-knit mixed-species flocks (Collins 1999).

DIET:

During fall and winter, Rufous-crowned Sparrows primarily eat small grass and forb seeds, fresh grass stems and tender plant shoots. Insects such as ants, grasshoppers, ground beetles, and scale insects make up only a small percentage of the fall/winter diet (11.6%) (Collins 1999). During the spring and summer the diet remains largely the same; however, insects make up a larger percentage of the diet (21%) and the species taken are more diverse (Collins 1999).

DRINKING:

It is unknown whether this species obtains adequate water from its diet or if dietary water must be supplemented by drinking. Individuals have been observed drinking from and bathing in pools of water in rock crevices following rainstorms (Collins 1999).

BREEDING HABITAT:

Rufous-crowned Sparrows are colloquially known as Rock Sparrows because of their distinct preference for open shrubby habitat on rocky, xeric slopes (Bolger 2002, Rising 1996a, DeSante and Geupel 1987). Throughout their range, they are typically found between 3,000 and 6,000 feet in elevation (Borror 1971). In California, they breed in sparsely vegetated scrubland on hillsides and canyons ranging from 60-1,400 meters in elevation (Rising 1996a, Collins 1999). Rufous-crowned Sparrows appear to prefer coastal sage scrub dominated by California sagebrush (Artemisia californica) (Grinnell and Miller 1944), but they can also be found breeding in coastal bluff scrub, low-growing serpentine chaparral, and along the edges of tall chaparral habitats. Rufous-crowned Sparrows thrive in areas that have recently been burned, and will stay in such open, disturbed habitats for years (Rising 1996a, Collins 1999). Rufous-crowned Sparrows exhibit high nest-site fidelity, returning to the same location to nest in subsequent years (Morrison et al 2004).

NEST SUBSTRATE:

Rufous-crowned Sparrow nests are primarily constructed of coarse dried grasses and rootlets, sometimes with small twigs, weed stems, or strips of bark (Myers 1909, Rising 1996a, Collins 1999).

HEIGHT OF NEST:

Rufous-crowned Sparrows are ground-nesters (Rising 1996a, DeSante and Geupel 1987). Infrequently a nest will be situated in a low bush up to 45 cm from the ground (Wolf 1977).

NEST CONCEALMENT:

Nests are usually well hidden, often situated at the base of a low bush, grass tussock, or overhanging rock with the overhanging vegetation or rock concealing its location (Rising 1996a, Collins 1999).

VEGETATION SURROUNDING THE NEST:

In California, Rufous-crowned Sparrow nests were found under California sagebrush, deer weed (Lotus scoparius), giant rye (Leymus condensatus), white sage (Salvia apiana), manzanita (Arctostaphylos spp.), poison oak (Toxicodendron diversiloba), coastal goldenbush (Isocoma menziesii var vernonioides), morning glory (Calystegia macrostegia), and bunchgrass (Collins 1999).

NEST TYPE:

The nests of Rufous-crowned Sparrows are loosely constructed, bulky, thick-walled open cups (Rising 1996a).

BREEDING BIOLOGY:

TYPICAL BREEDING DENSITIES:

Male Rufous-crowned Sparrows defend territories year-round; in the breeding season, one territory supports approximately one pair of birds, although unattached individuals have occasionally been documented in territories with established pairs (Collins 1999

DISPLAYS:

Male Rufous-crowned Sparrows maintain territories throughout the year (Collins 1999). The male will sing persistently on territory throughout the breeding season, especially at song posts defining territory boundaries. During interactions between males either at territory boundaries or during territory intrusions the males occasionally raise their crowns and face the ground to exaggerate their head patterns. In lengthier encounters the males will exhibit an aggressive display in which each assumes a posture in which the body stiffens, wings droop, feathers (especially on the rump and flanks) are erected, tail is cocked at a 45 degree angle, and the head is extended straight out or pointed upwards to accentuate the markings on throat for the other bird (Collins 1999).

Three decoy displays have been recorded for the Rufous-crowned Sparrow: tumbling

off a bush, rodent runs, and broken wing displays (Collins 1999).

MATING SYSTEM:

Rufous-crowned Sparrows are apparently monogamous; there are currently no reports of polygamy. Pair bonds appear to be maintained throughout the breeding season and possibly year round (Rising 1996b), with an apparent majority of birds staying paired for multiple breeding seasons (Morrison et al 2004).

CLUTCH SIZE:

Rufous-crowned Sparrows usually lay clutches of three to four eggs, occasionally two or five (NatureServe 2005). Average clutch size over the entire range is 3.5 +/- 0.68. Clutch size varies geographically, with the largest average clutch size in southern California at 3.7 and the smallest clutch sizes in Arizona and New Mexico at 3.1 eggs per clutch (Collins 1999).

INCUBATING SEX:

Only the female incubates (Rising 1996a). It is unknown whether the female begins incubation immediately after laying the first egg, or if incubation is delayed until the entire clutch has been deposited.

INCUBATION PERIOD:

Based on limited observations in southern California, incubation appears to last 11 to 13 days.

DEVELOPMENT AT HATCHING:

Chicks are altricial. On day three nestlings are still naked but with wing quills beginning to show (Myers 1909). There is currently no information available on the growth of contour and flight feathers or length of time after hatching when the eyes open. No quantitative data exists on weight or linear measurements of nestlings.

NESTLING PERIOD:

No quantitative data is available but the nestling period is estimated to be eight to nine days (Collins 1999).

PARENTAL CARE:

The female begins brooding immediately after hatching occurs and is the only parent to brood. Both parents bring whole adult insects to feed the young (Collins 1999). The entire insect is shoved into the gaping mouth of the nestling. Frequency and duration of food delivery visits and the number of items delivered per visit are unknown.

POST FLEDGING BIOLOGY OF OFFSPRING:

Fledglings are incapable of flight upon departure from nest, and spend their first days out of the nest running on the ground under the cover of vegetation (Collins 1999). Both parents continue to feed the young for some time after they have left the nest, but the exact duration of post-fledging parental care is unknown. Parents and juveniles probably remain together as a family unit through the post-fledging period and possibly well into winter. Most young birds are capable of feeding themselves by early fall (Collins 1999).

POST BREEDING SOCIAL BEHAVIOR:

Males maintain territories year-round. After chicks have fledged they forage in small family groups.

DELAYED BREEDING:

Age at first breeding is unknown. Young establish pairs the spring before their first breeding season, but it is unknown whether this occurs during their hatch year or later. Adult birds breed annually (Collins 1999).

NUMBER OF BROODS:

Rufous-crowned Sparrows are typically a single-brood species; second and third

broods have only been reported in southern California. Replacement clutches

are laid within one week of nest failure (Collins 1999). In areas with summer

monsoonal rains (Arizona, New Mexico, Texas and Mexico), Rufous-crowned Sparrows

can exhibit a bimodal breeding pattern. In such cases nesting occurs in April

through May and then again during the summer rainy season from July to early

September (Collins 1999, Rising 1996a).

BROOD PARASITISM:

Rufous-crowned Sparrows are rare hosts of Brown-headed Cowbirds, which are uncommon in the dry scrub habitat favored by the sparrows during the breeding season. There are only two records of parasitism by Brown-headed Cowbirds on Rufous-crowned Sparrows; one in a nest near San Antonio, TX and one in a nest in the Santa Catalina Mountains northeast of Tucson, AZ. Additionally, an unidentified cowbird chick was found in a nest at Madera Canyon, AZ. There is no evidence of brood parasitism by Brown-headed Cowbirds in southern California (Collins 1999).

LANDSCAPE FACTORS:

ELEVATION:

Rufous-crowned Sparrows inhabit suitable habitat from sea level to 3,000 meters (Collins 1999).

FRAGMENTATION:

Rufous-crowned Sparrows appear to be exceedingly sensitive to edge effects; Bolger (2002) found that Rufous-crowned Sparrows were abundant in larger tracts of habitat away from edges, and were quite rare in small isolated fragments of habitat.

PATCH SIZE:

Studies on the effects of patch size on Rufous-crowned Sparrow populations have focused on southern California populations. In an urbanized area of coastal San Diego County, Rufous-crowned Sparrows were more abundant in larger patches than in smaller, more fragmented patches (Bolger et al. 1997).

DISTURBANCE (natural or managed):

Rufous-crowned Sparrows are known to invade areas recently swept by fire or other disturbances. This species prefers open stands of chaparral and coastal sage scrub and will abandon an area if brush cover becomes too dense or too uniform. Episodic disturbances, including those caused by fire or light to moderate grazing, open up dense stands of chaparral and coastal sage scrub, improving habitat for Rufous-crowned Sparrows (Collins 1999, Bolger 2002; but see Stanton 1986).

ADJACENT LAND USE:

In southern California, habitat loss, degradation and fragmentation resulting from urban and agricultural development are restricting the range of Rufous-crowned Sparrows (Bolger 2002).

CLIMATE:

There is a significant positive correlation between Rufous-crowned Sparrow abundance and warm, dry weather (Bock and Lepthien 1976). In the Southwest, the occurrence of spring and summer monsoonal rains regulates the onset of breeding. However, it remains unknown to what degree the amount and duration of rainfall influences the breeding success of Rufous-crowned Sparrows (Collins 1999). Rainfall may indirectly affect breeding success through its influence on production of insect and seed crops as well as growth of herbaceous cover (Wolf 1977).

PESTICIDE USE:

One report exists of Rufous-crowned Sparrows being poisoned by the rodenticide warfarin (Collins 1999). More research is needed to explore the impact of small- and large-scale pesticide use on sparrow populations.

PREDATORS:

There have been no direct observations of predation on adults, eggs or nestlings. Rufous-crowned Sparrows are likely susceptible to avian predators that target passerines, as well as various reptilian and mammalian predators. In Arizona, Rufous-crowned Sparrows have been observed exhibiting aggressive vocal responses to a Mexican Jay and a tiger rattlesnake, suggesting that these species are likely nest predators (Collins 1999).

DEMOGRAPHY AND POPULATION TREND:

AGE AND SEX RATIOS:

No information is available.

PRODUCTIVITY MEASURE(S):

In southern California the seasonal fecundity estimates for one population of sparrows was 3.98 in 1996 and 4.86 in 1997. Of 35 nesting attempts, 17 (48.6%) successfully produced at least one fledgling (Collins 1999). No information is available on annual or lifetime breeding success.

SURVIVORSHIP:

Limited information exists on survivorship of Rufous-crowned Sparrows. In a four-year study in southern California, Morrison et al (2004) found that female Rufous-crowned Sparrows exhibited an annual survival probability of 0.69, while males had a slightly higher annual probability of survival, at 0.74. The study found no differences in survivorship between edge and interior habitats (Morrison et al 2004). Further studies throughout the range would elucidate clinal variations in survivorship.

DISPERSAL:

Birds generally remain on or near preferred breeding habitat during the fall and winter. Some post-breeding wandering of young birds and some adults to nearby non-breeding habitat has been observed (Collins 1999).

MANAGEMENT ISSUES:

HABITAT LOSS:

Loss of habit due to agricultural and urban development is the largest threat to Rufous-crowned Sparrows, particularly in southern California (Bolger 2002). Larger interconnected blocks of open coastal sage scrub on moderate slopes should be protected in order to insure population health. Rufous-crowned Sparrow habitat has been converted to range land for cattle throughout the species' range (Collins 1999). Limiting the duration and intensity of grazing will ensure Rufous-crowned Sparrows are still able to use this habitat. Fire suppression has also led to habitat loss, as Rufous-crowned Sparrows abandon dense, uniform stands of chaparral and coastal sage scrub. Controlled burn programs across the species range would benefit the species significantly.

ASSOCIATED SPECIES:

Greater Roadrunner (Geococcyx californianus), California Gnatcatcher (Polioptila californica), Sage Sparrow (Amphispiza belli).

MONITORING METHODS AND RESEARCH NEEDS:

A review of existing literature on the Rufous-crowned Sparrow in California reveals several areas where the need for further research exists. Although Rufous-crowned Sparrows can be quite difficult to monitor given their preference for high rocky slopes covered in chaparral, comprehensive studies of demography and nesting behavior must be conducted in order to develop a clear understanding of the biology and ecology of this species. In particular, information regarding age and sex ratios, survivorship, mating systems, nest success, incubation, nestling and fledging periods, and juvenal dispersal is still lacking for this species, as well as details of predation on nests and adults, and the impacts of invasive species and pesticide usage.

Constant-effort mist netting and observation of color-marked populations will

elucidate demographic trends, while nest monitoring will be necessary in order

to answer the many remaining questions about the reproductive behavior of the

Rufous-crowned Sparrow.

SPECIES: Rufous-crowned Sparrow, Aimophila ruficeps

STATUS:

There are 17 recognized subspecies of Rufous-crowned Sparrows, three of which (A. r. canescens, A. r. obscura, and A. r. ruficeps) occur in California. Rufous-crowned Sparrow populations within California are declining, largely due to habitat degradation, and the canescens subspecies is listed as a species of special concern by the state of California (CDFG 2004).

HABITAT NEEDS:

Rufous-crowned Sparrows require open coastal scrub and chaparral on medium to steep slopes, at elevations ranging from 60 to 6,000 meters. This species will abandon areas where sage scrub or chaparral has become too dense or uniform. They nest in shrubs such as California sagebrush (Artemesia californica), manzanita (Arctostaphylos spp.), and poison oak (Toxicodendron diversiloba), as well as morning glory (Calystegia macrostegia) and native bunch grasses. Edge effects do not appear to have an impact on reproductive success of Rufous-crowned Sparrows; however, birds apparently avoid edges and small fragments of habitat (Bolger 2002).

CONCERNS:

There is still a great deal to be learned about the breeding biology, behavior and demography of the Rufous-crowned Sparrow. Details about reproductive timing, nestling growth, and dispersal will be vital for the development of conservation plans that encourage appropriate Rufous-crowned Sparrow breeding habitat, and standardized abundance, productivity and survivorship data are necessary in order to detect population declines, and to evaluate the effects of habitat alteration and management regimes. The preeminent threat to Rufous-crowned Sparrow populations in California is habitat loss. Large areas of coastal sage scrub and chaparral, particularly in southern California, are being converted to urban and agricultural land. Additionally, fire suppression practices over the last one hundred years have led to dense, uniform stands of sage scrub and chaparral unsuitable for the Rufous-crowned Sparrow, which prefers more open scrub habitat.

OBJECTIVES:

1. Preserve and increase available habitat

2. Identify healthy populations, and elucidate long-term trends

ACTIONS:

1. Preserve areas of coastal scrub and chaparral that currently provide appropriate habitat for Rufous-crowned Sparrow by acquiring lands currently held by private landowners, and by encouraging active conservation and restoration on public lands.

2. Preserve and restore contiguous tracts of scrub habitat that have been altered by fire suppression, invasive plant species or other anthropogenic factors. This will require land acquisition and intensive restoration efforts. Although the productivity of Rufous-crowned Sparrows does not appear to be affected by patch size, Bolger (2002) found that the sparrows showed a preference for larger patch sizes. Ensuring the protection of contiguous tracts of coastal scrub and chaparral will encourage healthy populations of Rufous-crowned Sparrows. Restoration of altered habitats might entail prescribed burning, limited grazing, or removal of exotic plant species.

3. Establish long-term demographic monitoring for the species in order to assess the health of California populations. Because Rufous-crowned Sparrows are sedentary, color-marking and re-sighting individuals and conducting nest monitoring will be the most appropriate methods for tracking abundance, productivity and survivorship.

4. Provide outreach and education in suburban and urban areas adjacent to coastal scrub and chaparral habitats to encourage native plant landscaping and low-impact building. Encouraging public buy-in is an essential ingredient in successful habitat conservation and restoration. Developing pamphlets and other informational materials encouraging the use of native plant landscaping, removal of non-native plant species and active management of remaining coastal scrub and chaparral habitats will allow individual stakeholders to participate in the conservation process.

Bock C.E. and L.W. Lepthien. 1976. A Christmas count analysis of the Fringillidae. North Amer. Bird Band. 47(3): 263

Bolger D.T. 2002. Habitat fragmentation effects on birds in southern California: contrast to the "top-down" paradigm. In T.L. George and D.S. Dobkin, eds. Stud. Avian Biol. 25: 141-157

Bolger D.T., T.A. Scott and J.T. Rotenberry. 1997. Breeding bird abundancein an urbanized landscape in coastal southern California. Conserv. Biol. 11: 406 - 421

Borror D.J. 1971. Songs of Aimophila sparrows occurring in the United States. Wilson Bull. 83(2): 132

Collins P.W. 1999. Rufous-crowned Sparrow. In A. Poole and F. Gill, eds. Birds North Amer. 472: 1 - 27

(CDFG) California Department of Fish and Game. 2004. California Natural Diversity Database (CNDDB) special animals. Available from: http://www.dfg.ca.gov/whdab/html/animals.html.

DeSante D.F. and G.R. Geupel. 1987. Landbird productivity in central coastal California: the relationship to annual rainfall, and a reproductive failure in 1986. Condor 89: 636-653

Grinnell J. and A.H. Miller. 1944. The distribution of the birds of California. Pac. Coast Avifauna. 27: 1 - 610

Miller A. 1941. Rufous-crowned Sparrow of southeastern New Mexico. Auk 58(1): 120

Morrisson S.A., D.T. Bolger and T.S. Stillett. Annual survivorship of the sedentary Rufous-crowned Sparrow (Aimophila ruficeps): no detectable effects of edge or rainfall in southern California. Auk 121(3): 904-916

Myers H.W. 1909. Nesting habits of the Rufous-crowned Sparrow. Condor 11: 131

- 134

NatureServe Explorer. 2005. Natural Heritage Network: Rufous-crowned Sparrow.

Available from: http://www.natureserve.org/explorer/

Power D.M. 1994. Avifaunal change on California's coastal islands. Stud. Avian Biol. 15: 75-90

Rising J.D. 1996a. A Guide to the Identification and Life History of the Sparrows of the United States and Canada. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. 365pp.

Rising J.D. 1996b. Relationship between testis size and mating systems in American sparrows (Emberizinae). Auk 113(1): 224-228

Stanton P.A. 1986. Comparison of avian community dynamics of burned and unburned coastal sage scrub. Condor 88: 285-289

Wolf L.L. 1977. Species relationships in the avian genus Aimophila. Ornith.

Monogr. 23